By Dr Sarah E Hayward and Dr Stephanie Stroh

Back in January 2024, I had the great pleasure of sharing Lucy’s Story with you. It’s a story I had ample time to develop and refine – to shape into a video essay, to recount and reflect on in my PhD research, to present at conferences, and finally to publish in ALISS Quarterly (Volume 19 No.2). Just as I’ve treasured telling and retelling Lucy’s Story, it has always been with an awareness that so many others remain untold.

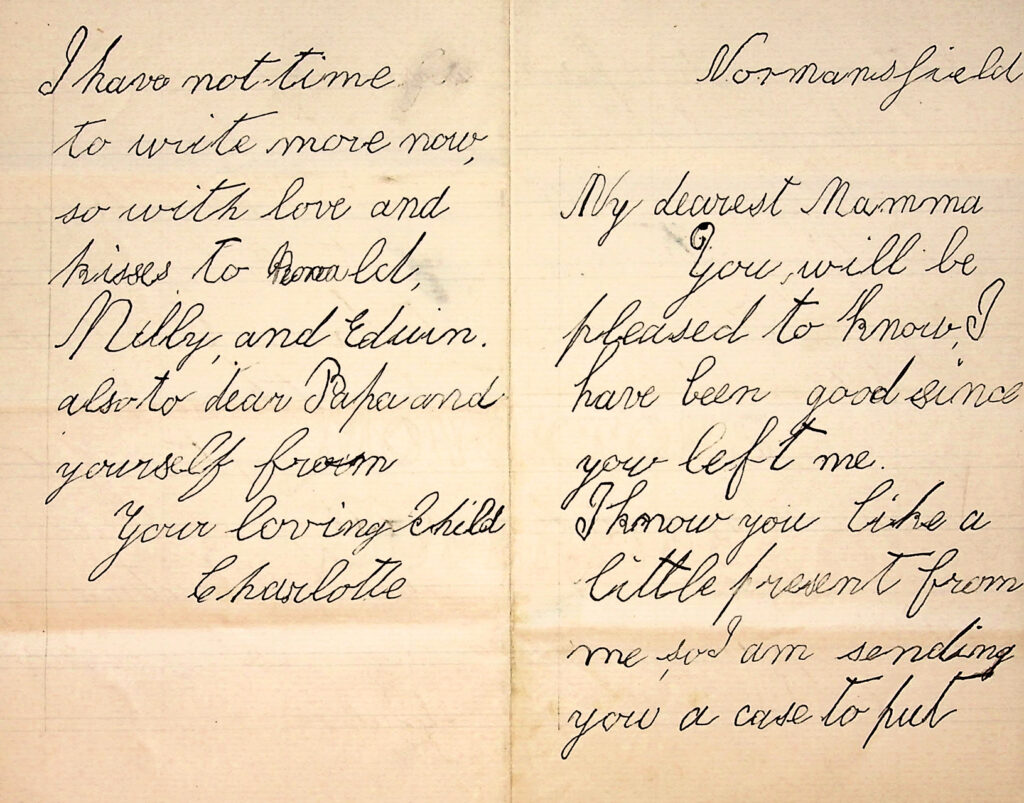

A residential school established in 1868 by John and Mary Langdon Down, Normansfield Hospital was a private institution that cared for the children and family members of society’s elite classes. One of those children was Charlotte Adelaide Harris. Charlotte was one of several Normansfield residents I came across during my research but was unable to pursue further at the time. Now, working with fellow researcher Stephanie Stroh, we’ve been able to trace her journey more fully and bring her story to light.

On Wednesday, 10 October 1883, 13-year-old Charlotte is admitted to Normansfield. She comes from an upper-class family in Ontario, Canada, brought over by her parents, who hope her condition will improve under the Langdon Downs’ care. Charlotte has suffered from epilepsy since early childhood, a condition nineteenth-century contemporaries found both perplexing and frightening, and which, in medical circles of the day, was often discussed alongside learning disability.

Upon arrival, her mother fills out the admission form in which Charlotte is classified as a “person of unsound mind.” Two separate Medical Certificates confirm this assessment. The doctors observe that she is “very irritable,” “fidgeting about continually” and touching “everything in the room.” She is unable to state when she was born, count from 1 to 50, or respond adequately to a question asked. The Medical Casebook further reveals that “she is unable to dress herself completely. She can read a little and speaks but indistinctly. There is no history of Insanity in the family.” Charlotte – now patient 294 – is prescribed potassium bromide, a common treatment for epilepsy at the time, and settles into the institution where she will spend the following two-and-a-half years away from home and family.

Charlotte first stood out in the archives due to the volume of correspondence sent by her mother. In April 1885, for instance, the Langdon Downs receive eight letters from Mrs Harris. She begins with a discourse on Charlotte’s hair, then her jacket, and worries about a cough, “especially when all these East winds give one no chance of being better.” Mid-month brings an overdue cheque from Mr Harris. By month’s end, Charlotte’s parents have returned from a sojourn on the Isle of Wight and write that they are eager to see her again. Of the 127 letters held in the Normansfield Archive Collection (NAC), almost all are written by her mother. Collated and read in chronological order, they immerse the reader in the experiences and thoughts of Mrs Harris – a woman juggling family responsibilities, social expectations, and an often-palpable sense of inner turmoil.

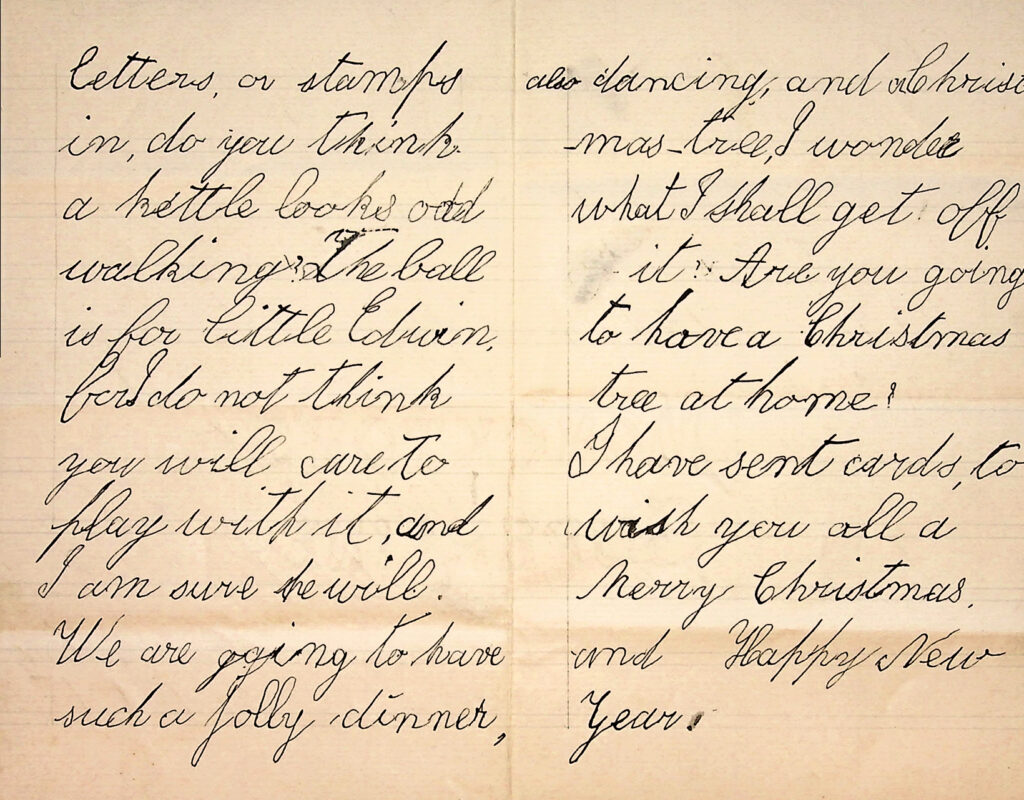

All the information we had gleaned about Charlotte up to this point is rendered by her mother, speaking of Charlotte, describing her needs and appearance, reporting on her character and health. ‘Charlotte’ gradually materialises through and between the lines of her mother’s narrative: ‘Chassie’ enjoys bathing in the sea; she is anxious to return to Normansfield following short trips with the family; she wears a white woollen shawl over her shoulders in bed; she forms friendships with other patients. As the letters float freely in and out of the hospital’s solid walls, Charlotte receives petticoats, dresses, Christmas cards, books, sweets, a coral necklace, a toy, and a picture of her brother.

Far from being the end of Charlotte’s story, however, this correspondence also reveals the existence of another voice. In November 1883, Mrs Harris remarks that Charlotte’s “letter was neatly written,” and eleven months later, attests that “her last little letter was decidedly better written, her hand firmer and less shaky.” These remarks, though concerned only with her abilities, indicate that Charlotte is writing herself – an insight that sends us in search of further evidence, and eventually leads to another archive an ocean away.

The first discovery is that Mrs Harris has sections of her diaries published in The Eldon House Diaries: Five Women’s Views of the 19th Century. Herein, we are taken back in time to Charlotte’s birth on the 28th of June 1869 and discover her mother’s subsequent concerns over her health and development. When Charlotte is five, her mother laments: “My poor child. How hard it will be for her who cannot speak at all to tell what she wants.” Charlotte develops convulsions: “I ran up, put her in a hot bath and wrapped her up in blankets. She then had a second one. The doctor came. He thought it was worms.” Within the month, she is diagnosed as epileptic: “My worst fear is realised.” The doctor prescribes “70 drops three times a day” and a T-bone neck support, hoping to ease “the congestion of the brain” and that “she might get perfectly well in a year.” This is not to be, however, and the diary leads us back full circle to Charlotte’s admittance to Normansfield Hospital, and thus its Archive Collection.

With Charlotte settled at Normansfield, and their other children in boarding school in the West Country, Mr and Mrs Harris remain in Europe for two years, dividing their time between travel and being near their children. In early 1884, they tour France and Italy. Charlotte later joins them in Bath for a short stay: “I am sure Charlotte is happy with you for she was extremely anxious to return. We found her grown and I think better in very many ways.” They spend several months the following year on the Isle of Wight, always keeping in close contact. In the autumn of 1885, however, Mr and Mrs Harris set sail home to Canada, Mr Harris noting: “I can get any letters from you in about 11 days if a quick steamer.”

Throughout the letters, we know that Charlotte is frequently unwell. In 1886, the Medical Casebook reports that she has developed abscesses on her body which “discharge freely,” sapping her strength:

July 31: “Symptoms of collapse in morning. Ordered a teaspoonful of brandy every two hours. 4 p.m. rallied, quite conscious but restless.”

August 1: “Breathing embarrassed. Temp 103° in the morning. 11 a.m. breathing still shorter. 12 noon died. Notice sent to the Coroner.”

The published diaries lead us to ‘Eldon House,’ home to four generations of the Harris family, and gifted to the city of London, Ontario, in 1960 – opening as a museum a year later. The entire family archive, dating from 1794 to 1959, survives a couple of miles down the road at Western University (WU). Thanks to the digitising efforts of their research support team, we gained access to a treasure trove of diaries, photographs, and letters, including what we had never imagined seeing – Charlotte’s own letters. What started place-bound with bundles of correspondence at the London Archives grew into a vast and varied collection, and opened research pathways beyond institutional boundaries.

Histories of Victorian institutions like Normansfield are largely represented through the published words of those who founded or worked in them, and through the administrative documents left behind, rather than the voices of those who lived within. Thanks to our two archives, however, we have so much more.

As Charlotte’s health fails and she passes away, Mrs Harris writes daily in her diary of illness and exhaustion, often with headaches, and mourns her daughter deeply. If we bring our two archives into conversation, they begin to reveal a deeper, more textured narrative:

(WU) August 2nd, diary: “A letter from Mrs Down saying there is no hope. Oh, to think I shall never see her poor face again or feel her little arms around me.”

(WU) August 3rd, diary: “My poor darling is free from pain. Her life was one long agony… I should have loved to think her poor little body would have laid beside her brother and grandfather, but this cruel trouble of Edwards has robbed me of home and ever the means of placing my child in the grave I should have liked.”

(WU) August 4th, diary: “Poor Charlotte. My prayer has been that she might go first, and I might be spared the pain of leaving her. Thank God her sufferings are ended, and she is at rest and free from sorrow.”

(WU) August 12th, diary: “My poor dead Charlotte. I think often of you, free and happy at last, after all your bitter pain and sorrow, dear lamb, safe in the Fathers arms. He alone knows why your little life was so full of pain, and has taken you to rest.”

(WU) August 19th, diary: “Today at 11am this place is to be offered for sale. Here we have had all our married life. Our children born and my dear mother died in the next room. My poor Charlotte gone. In going to Eldon, I go to a house not a home.”

(NAC) October 3rd, letter from Mrs Harris to Mary Langdon Down: “I feel my little girl had every care and attention during her illness. Normansfield has made a happy home to her, for when she paid us little visits she always wished to return and spoke with warm affection of her attendance.”

(WU) October 16th, letter from Mary Langdon Down to Mrs Harris: “We are always glad we can remember dear Chassie as being perfectly happy with us – even though for so long she was such an invalid.”

(WU) December 24th, diary: “Christmas Eve. Oh, how sad my heart feels. How will it all end and where will we be next year, I wonder. My poor Charlotte in her little grave so far away from us all. But her poor little body is free from pain, and she is safe from all that sorrow.”

This mother’s mourning, recorded in letters and diaries, is deeply moving, and our journey of discovery has been both exciting and challenging. Confronted with the vastness of material that emerged, we know our research has only scratched the surface – and we feel a certain responsibility to continue. We also wonder: has this work brought us any closer to Charlotte, who, unlike her mother or sister Milly, remains under-represented, and at times absent, in the Harris family’s material culture and memory?

Reassembling and sharing Charlotte’s story contributes new knowledge to the history of learning disability. It brings to light, and to life, part of a largely hidden and marginalised heritage. Through our research, we are always seeking, as far as possible, to represent the perspective of those at the heart of the narrative – the patients of Normansfield Hospital.

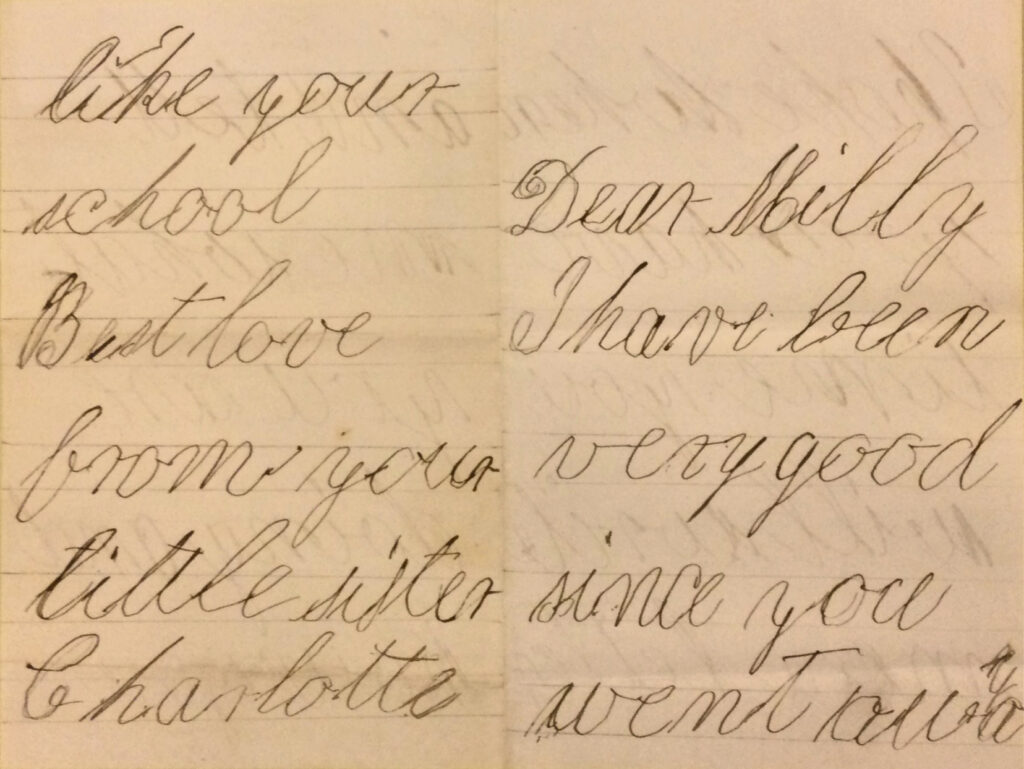

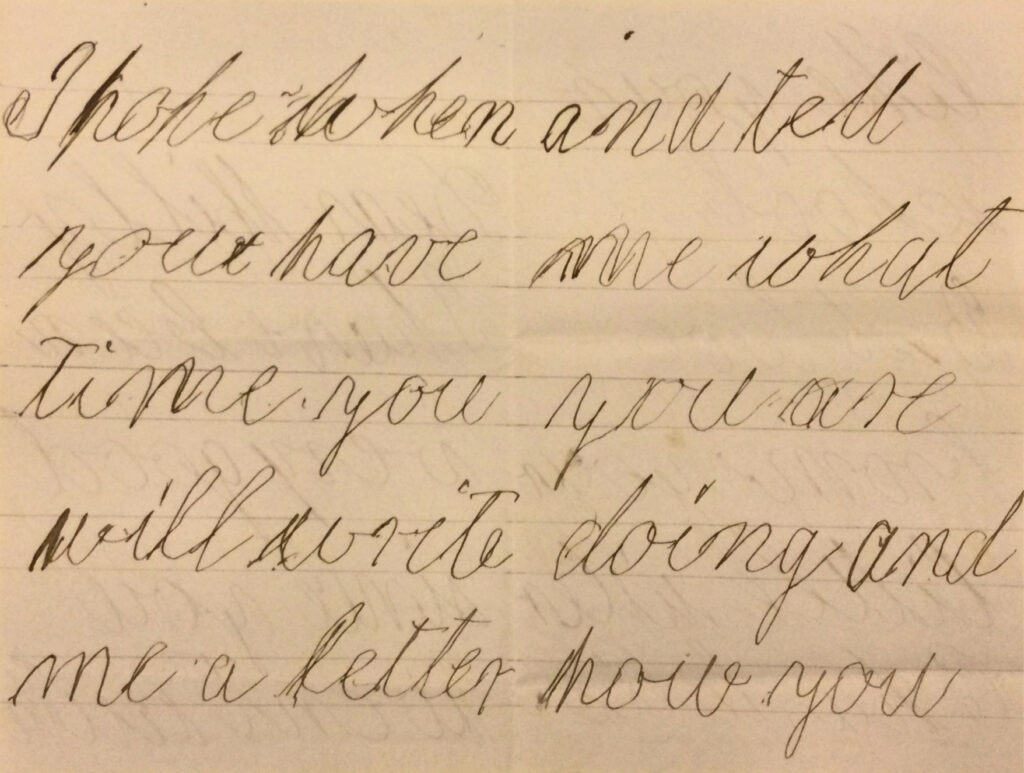

The correspondence above is shaped by social expectations and propriety, while the diaries offer a private, introspective refuge. The ‘Charlotte’ they construct is an assemblage of subjective voices. Yet we do have Charlotte’s own voice – preserved in a few precious letters that moved us deeply. We have reserved them until the end, inviting you to pause and consider how her own words might shift what you’ve come to believe about her life.

Western Archives and Special Collections, Western University, AFC 48, John and Amelia Harris Family fonds, Correspondence To Milly Harris and From Charlotte Adelaide Harris, undated.

Western Archives and Special Collections, Western University, AFC 48, John and Amelia Harris Family fonds, Correspondence To Lucy Harris and From Charlotte Adelaide Harris, undated.

References and Resources:

Dr Sarah E Hayward, ‘Lucy’s Story: A Gift from the Normansfield Archives’ ALISS Quarterly Volume 19 No.2, January 2024

Robin S. Harris and Terry G. Harris, eds., The Eldon House Diaries: Five Women’s Views of the 19th Century (The Champlain Society: Toronto, 1994)

The Normansfield Archive collection is held at the London Archives, ref. code: H29/NF

Eldon House had a dedicated website: https://eldonhouse.ca/

The Harris Family Fonds are deposited at Western Libraries, ref AFC 48